|

Volume

69, pages 572-573, 1984

Presentation of the Roebling Medal of the Mineralogical Society of America

for 1983 to

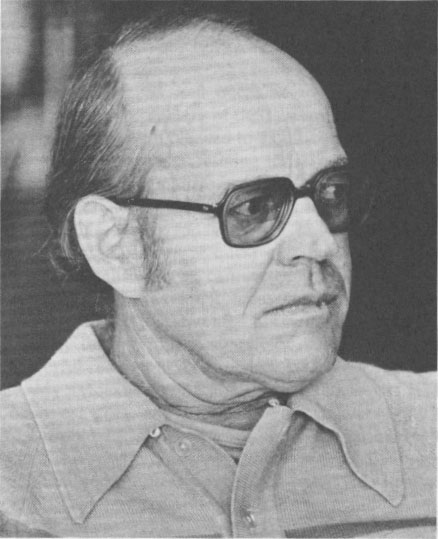

Hans-Peter Eugster

DAVID R. WONES Department of Geological Sciences

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Blacksburg, Virginia 24061

Officers and members of the Society, and guests:

Today I have the privilege of introducing to you one of our outstanding

members as the Roebling Medalist. I have known the man for a quarter of a

century, and continue to be rewarded by his friendship, his personal

generosity, his demand for truth, and by his creativity. Those of us who

have had the good fortune to have Hans Eugster as our mentor have sensed

from the start of our apprenticeships that we were truly colleagues in the

effort to better understand rocks and minerals. This feeling of selfworth

is the greatest gift one human can bestow on another, and Hans has

showered it on his students in great abundance.

Those who have visited Hans' rural retreat in Maryland can also attest to

his generosity as a host and to his abilities as a chef and raconteur. He

has a wonderful sense of humor which has served him and his colleagues

well over the years. I remember well the tenseness of the situation when

he, the Swiss, was correcting and improving the english in my

dissertation. His good humor made me come out of the encounter grateful

for his suggestions, and more importantly, happy about myself and my work.

His generosity is given freely, not only on things mineralogical, but on

food, wine, music and art. This generosity has been freely given to us

even when Hans himself was going through his own physical and emotional

traumas. A wonderful by-product of being an Eugster Associate is the sense

that we all are part of a family, and some of my longest and truest

friendships with graduates of Johns Hopkins University began during our

mutual association with Hans. I don't know if Hans was a scout in his

native Switzerland, but his personal qualities read like the Scout Law:

his regard for the truth; his kindness to his students; his bravery under

physical ordeals; and his reverence for the world, its people, and our

science.

Two exceptional personal qualities which have brought Hans to this podium

today are his quest for truth, or if you will, his curiosity, and his

creative ways in finding that truth. When I was struggling with some

apparent discrepancies during our early collaboration, I finally came to

the conclusion that some of my original temperature determinations must

have been in error. I reluctantly spoke about this to Hans, and the

immediate retort was to find out why. Thus began my initiation into why

one never takes any sort of laboratory measurement for granted. The consequent corrections led to a consistent set of

measurements, and our work was on its way. I then learned the true meaning

of "the truth shall set you free." During that work we had

occasion to summarize the thermodynamic parameters of the system Fe-Si-O

twenty years ago, and I am pleased to say that Hans is the coauthor of a

recent paper refining these parameters. His quest for the truth remains

vigorous.

Eugster's creative genius is the other reason we are celebrating his

career today. When I was visiting the Geophysical Laboratory in quest of a

possible doctoral thesis, his inventive ideas captured me in the way that

N. L. Bowen's ideas must have captured an earlier generation. He had just

invented his buffer method, and I was greatly taken with the simplicity of

the device, and the powerful reach that its application would give

mineralogy. My association with Hans and his ideas has given me countless

gifts, and I remain in awe of his ability to grasp a problem ("Dave,

you haven't come to grips with the problem" was a constant

invocation), see the essential conflict, and propose a dozen solutions. He

remains a disciple of multiple working hypotheses, and through this,

continues to create new interpretations and methods for discovering the

truth. I hasten to add that his mind is not only creative, but also facile

and tough. Part of our original collaboration was possible because of my

formal training in chemical thermodynamics which Hans had not had. For a

few months, I was the teacher and he the student, but he quickly absorbed

what I knew, set off on his own, and began to teach me new things and new

methods. His recent work on the Cornwall Pennsylvania Magnetite deposits

and his paper at this meeting on tin deposits in China demonstrate his

firm grasp of thermodynamic methods, and his uncanny ability to create new

applications.

His creativity rubbed off on all of his students, and through us, Hans has

given the world oxygen, hydrogen, water, carbon dioxide and halogen

fugacity meters, geologic thermometers, properties of minerals and other

phases of geologic interest, and methods of attacking problems in all

phases of petrology: igneous, metamorphic, ore deposition, and

sedimentology. His early recognition that the evaporite minerals of the

Green River formation were the product of a history of aqueous processes

started him on a series of major contributions of ideas, data, and students to chemical

sedimentology. His influence has been felt so pervasively

that now it is

commonplace to interpret sedimentary mineral assemblages to reveal the history of

H2O

interactions in those rocks.

Mr. President, for

these many contributions to our science - his students, his colleagues, his inventions, his ideas, his vision of a

coherent science of mineralogy - I am pleased and proud to introduce Hans-Peter

Eugster, the 1983 Roebling Medalist.

Volume

69, pages 574-575, 1984

Acceptance of the Roebling Medal of the Mineralogical Society of America

for 1983

HANS-PETER EUGSTER Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences

The Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, Maryland 21218

President Roedder, Members of the Society, Guests:

One hundred years ago this spring, a bridge built by John Augustus

Roebling, father, and Washington Augustus Roebling, son, was dedicated

which to this day connects Brooklyn with Manhattan across the East River.

The son, of course, is the reason why I'm privileged to stand before you

today and why it is appropriate to use the bridge as the theme of my brief

remarks. John Augustus Roebling, or if you permit me to deanglicize his

name, Hans-August Röbling, was born in Prussia in 1806. Hans-August was

his first name, just like mine is Hans-Peter, shortened for American usage

to Hans or John. After studying civil engineering in Berlin he moved to

Pittsburgh, where he began to realize his central idea: building of

bridges supported by wire ropes or steel cables. Starting with an aqueduct

across the Allegheny River, graduating to a combined road-railroad bridge

over the Niagara Falls, he finally gave his life to the Brooklyn bridge.

He died of tetanus in 1869 after being injured while laying out the

supporting towers.

Washington Augustus Roebling completed the bridge and added to the

achievements of his father. He had the leisure and means to assemble a

remarkable mineral collection and to generously endow the Mineralogical

Society of America. Today I am the immediate beneficiary of his

generosity. In the early fifties, when we were synthesizing layered

silicates, I frequently used his collection, housed in the Smithsonian

Institution. I particularly remember specimen R4416, a fine paragonite we

used as starting material. During those happy years at the Geophysical

Laboratory, I was, in fact, working as a mineralogist, synthesizing

minerals and defining their thermal stabilities, chemical and X-ray

properties. What I have done since hardly fits the mold of a mineralogist,

either of the geometric kind exemplified by my late teacher Paul Niggli,

or of the modern TEM type represented by my office neighbor and

cocelebrant, Dave Veblen. Why then should I be honored today by the

Mineralogical Society, for work in experimental petrology, geochemistry

and sedimentology? Aside from the very generous interpretation of their

charge by the selection committee, it points to the role of mineralogy as

a bridge. Paul Niggli, in one of his philosophical essays, spoke of

crystallography and mineralogy as the glue, which binds together the

natural sciences through the concept of order in the solid state. Glue or

bridge, the architecture of the solid state certainly is a central theme for physics,

chemistry, biology and geology and the Niggli message was not lost on me.

However, I also belong to the lucky generation of geologists who came into

their own after the war. We had new toys and new thoughts and could try

anything once and almost everything worked. I agree with Connie Krauskopf

that the real revolution in the earth sciences was initiated in the

fifties rather than the sixties: the change from a largely descriptive to

a quantitative science. I remember buying the 1951 text on igneous and

metamorphic petrology by Turner and Verhoogen and taking it into the

Canadian bush where it competed for my attention with black flies.

Verhoogen's sections baffled me but I couldn't let go. I finally mastered

that material years later after I started teaching it at Johns Hopkins.

Building a bridge from chemistry to geology became and still is a passion

for me, but building bridges depends on having strong anchors and towers

in the lands to be joined, as John Augustus Roebling knew. My anchor in geology was built while I labored on my

thesis, mapping metamorphics in the Alps, and I feel good about it, but my

tower in chemistry is another matter. Its foundation, also built in

Switzerland, is sound, but it pointed in the wrong direction. I was taught

how to analyze rocks, but I never had a course in physical chemistry or

thermodynamics and hence those symbols of Verhoogen looked so strange. I

am still building and shoring up that structure and I have been lucky to

have smart people teaching me during the last 25 years, from Dave Wones to

John Weare. Dave was my first student and, although he'll tell you

otherwise, he taught me more than I taught him. He got his Ph.D. from MIT

and I never had to read his thesis and perhaps that is why we are still

good friends. Dave was followed by a string of students too long to

mention, but each one helped eradicate another corner of my ignorance.

Just about the time Dave was finishing his thesis, I was asked to review a

paper by Charles Milton on the Green River minerals and this started me on

a second track which only now is becoming integrated with my earlier

interests. I cannot explain my continued fascination with salt lakes. In

fact some of my friends gently chided me for escapism and wasting my time.

That may be, but it has been an enormous source of fun, excitement and

adventure. Initially it was just Blair Jones and I and then Laurie Hardie

joined us. Here too, bridges had to be built, from mineralogy to water

chemistry to sedimentology and even to organic geochemistry. For our

recent study of Great Salt Lake, for instance, Blair and I assembled a

dozen specialists to carry out the necessary work and we learned what it

means to organize a research team. Clearly both of us prefer one-on-one

collaboration.

Although I do not consider myself to be a mineralogist, minerals and

mineral assemblages remain near the center of my interests. Looking back

over 30 years to the days when Hat Yoder first introduced me to the world

of hydrothermal synthesis, I realize that the central theme has been and still is the interaction of minerals with aqueous fluids,

from surface waters to geothermal brines to metamorphic fluids to igneous

gases; a bridge carrying water just like Roebling's aqueduct over the

Allegheny River. Even my newest venture into ore deposits is launched from

a watery base.

To thank all those who have helped me in my scientific endeavors would be

name dropping and selecting among my teachers, students and colleagues is

too difficult. There are three people, however, that I feel compelled to

acknowledge. Blair F. Jones, an early student, longstanding friend,

colleague and perennial coauthor: You make it look as if it is easy to

work with me, a precious illusion not shared by many. Bob Houston,

southern gentleman and Indian expert of Laramie, Wyoming: You have prodded

me into my new venture; the geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits and

your friendship and the snow in the Rockies are the reasons for my yearly

treck west. Finally, Elaine Koppelman, the James Beall Professor of

Mathematics at Goucher College. Those of you who teach are familiar with

the five-minute panic, when five minutes before the lecture an equation

suddenly looks mysterious and unfathomable. As the clock ticks away and

desperation mounts, you consider whether you should declare yourself sick,

run away, commit suicide or just brazenly pretend to understand. That's

when I call Prof. Koppelman who then calmly clarifies that tricky

derivation. During the summer months she acts as my most trusted and

capable field assistant, and unhesitatingly follows me to the salt lakes

of Africa and the high Andes or the tin mines in China. She is also an

excellent cook and, as my wife, makes life worth living. A native of

Brooklyn, she is very much connected with the Brooklyn Bridge and hence to

the father and son team of J. A. and W. A. Roebling. I accept this medal

for both of us and we thank you for this honor and for including us in the

brotherhood and sisterhood of mineralogists. Thank you very much.

Footer for links and copyright

|